"YOU SHOULD WRITE THAT LETTER," Paul Weller is telling his press agents, Pippa Hall and Jane Wilkes of Monkey Business PR, referring to a particularly unpleasant review by Caroline Sullivan in The Guardian of his summer concert in Hackney's Victoria Park, and to the missive he is requesting that Pippa and Jane fire off in response. Then he turns towards Uncut. "Did you read what she wrote about Ian Dury? He did that gig with us, and she was more or less saying the only reason Ian Dury was on the bill was because he's dying of cancer. Pippa and Jane are going to write to them. Fuckin' should do, man. And then Geldof [after mistakenly announcing Dury's death on XFM] played 'Reasons To Be Cheerful'. Fucking Dick. "Those so-called quality papers, The Guardian and all the others, have descended to that shit. Fucking hacks, man. It's all this sort of personality thing. The last two interviews I did were, 'What restaurants do you like?' Any fuckin' restaurant. And, 'What sort of shops do you shop in?' Nothing about music. You could tell they ain't got a fuckin' clue. Fucking sad." This isn't the first thing Paul Weller says to me on this warm late-September Tuesday afternoon, down in the Monkey Business bunker. The first is to enquire whether I want anything to eat because he's come all the way from Woking on the train, he's starving and he's off out for a burger and chips. The second is to thank me for a tape I made for him recently of Brian Wilson's second, unreleased solo album (Weller liked Uncut's cover story on the Beach Boy and wanted to hear what the fuss was about). The third is to cast aspersions on my boss, Allan Jones, and to compare him in less than flattering terms to a part of the female anatomy. Why? Because of a review he wrote for Melody Maker in July, 1988 of The Style Council's Confessions Of A Pop Group, in which he described Weller and erstwhile partner Mick Talbot as "the Don Estelle and Windsor Davies of supine albino funk". "Allan Jones," says Weller (favourite film: A Clockwork Orange), joining Uncut in the corner of the Monkey Business office, lighting the first of many Benson & Hedges, "is a c***. And you can tell him if he wants some, he knows where to find me. "Now, you might be thinking, this early on in Uncut's extensive Paul Weller retrospective, that here is a bloke who not only has a memory worthy of most elephants, but who is also unhealthily preoccupied with the vicissitudes of the Fourth Estate. I'm not convinced this is the motive for the abuse. My guess is he's testing the journalist's mettle, seeing whether I've got the bottle to stand my ground, checking whether I have the integrity to defend a colleague. So do I counter the harsh words of the bloke in the pinstripe suit and smart, pink shirt? Do I confront Mr. Sup Up Your Beer And Collect Your Fags and rally to protect the honour of the man to whom I owe my livelihood? Do I fuck. I laugh my bloody socks off, that's what I do. On the eve of the release of his 16th solo single, "Brand New Start", and a compilation of his solo work called Modem Classics ("That's truly what I believe they are," he will say later), Paul Weller has been invited here today to discuss not just his recent history as a solo artist, but to critique and dissect his entire 22-year career. Why Paul Weller? Because he is revered by indie, rock - even dance - cognoscenti. Because, although he may not possess the corrosive intelligence of his nearest rival, Elvis Costello, there's no denying the power and the glory of The Jam, the polish and melody of The Style Council, if not the coarse delights of his solo performances. And because, despite the fact that his critical stock has risen and fallen more often than the price of beef (he'd be the first to admit, indeed he does over the next two days, that he's made both good and bad records in his time), Weller is, commercially at least, the leading songwriter of the post-punk era. He fronted the most popular UK band of the late Seventies/early Eighties (read those old NME Readers' Polls, Ashcroft, Gallagher and Co., and weep), formed a second outfit who regularly graced the charts for a further six years, and has subsequently gone on to enjoy a third term in office (as it were), again lasting six years to date. Second comings we're used to. John Lydon disbanded The Sex Pistols to form PiL, Shirley Manson went from Goodbye Mr. MacKenzie to Garbage. John Squire left The Stone Roses for The Seahorses. But, with the exception of Bernard Sumner (Joy Division, New Order, Electronic), Peter Hook (JD, NO and Monaco) and Paul McCartney (The Beatles, Wings, solo), no one has endured in three completely separate incarnations, each one quite different from the last, covering a range of styles from punk-pop to funk, from neo-classical to gritty rock. It's official: Paul Weller is Britain's fourth most successful writer-performer of all time. According to The Guinness Book Of British Singles, he has had more self-penned hits (51, assuming "Brand New Start" does the business) than anyone save Paul McCartney (69), Elton John (62) and David Bowie (54, if you must include Tin Machine). Weller, affable, open and far more forthcoming than his reputation as paranoid humanoid led me to expect, is amused but not impressed by all these statistics. "Fucking hell," he says with a wry smile, "I should get something from the Queen." To Be Someone - The Jam

LET'S go back 21 years ... "If you must." Starting with In The City. is that a completely different Paul Weller who made that album? Do you recognise yourself in any of those songs? "Yeah, sure. Definitely. Any 18 -year-old or 17-year-old - or however old I was at the time - would recognise me." Would an 18-year-old now be able to associate and identify with the ideas and themes you were exploring on that debut? "I would have thought so. I don't think they're particularly brilliant songs, lyrically and stuff, but just the kind of urgency about it. Grrrrr. All that fucking stuff." If you had to pick the best tracks, what would they be? "Oh, In The City', definitely. It's a fuckin' teenage classic. 'Non-Stop Dancing' is good, I can still relate to the words in that. There's some bollocks like 'Time For Truth'. To be honest, that sort of pseudo-political thing was right out of my depth - that was more like The Clash. Reading stuff like Sniffin' Glue. People like Strummer saying, 'People should in writing about what's important now. This was my half-arsed attempt to do something like that." How did you feel when you met Strummer? "I liked him. He was much, much older than me." It's funny how attitudes towards age change. I remember when Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons were drafted into the NME to blow away "the old guard" - Nick Kent, Charles Shaar Murray and the rest, who must have been all of 25. "Well, Joe [Strummer] lied about his age." Did it really matter that much? Course it did, man. Don't you think?" More then than it does now? It's different now. People are much younger these davs. A person even my age can wear the same clothes as a teenager without looking a prat. It was more cut and dried. I bought the whole teenage rebellion thing." Is there anything to rebel against now? You can swear on TV, there's sex everywhere, you've got a rock'n'roll Prime Minister. . . There's always room for a bit of teen rebellion. Every generation comes up with something." In an us and them situation, who is "them" these days? Is it still the government? "I would have thought so, wouldn't you? Especially with these welfare laws they're bringing in. I'm getting into a conversation I know fuck-all about here, but it's like students having to borrow money to get their grants. It's an eternal battle." Is In The City up there with those other great punk debuts, Never Mind The Bollocks and The Clash? "Well, they didn't do much for me, to be honest with you. So I couldn't compare them. I thought it [punk] is a load of bollocks, actually. I thought it existed in the clubs, and once the bands got signed up, straight away it became something else." There were a lot of bands, but only three that mattered.

"There were a few others as well, stragglers, but the major ones, yeah. I never liked most of them, but I quite liked the attitude and the ideas. I took what I wanted from punk, made my own thing out of it. I thought most of the bands were real copouts." Weller was a renegade from the off: the black and white uniform, the Mod imagery, the admission of support for the Conservatives in an early NME interview . . . Did he feel like an outsider even during punk? "Yeah. And in the early days-even though I came in a bit late - most of the people I met were all trendy wankers. Once it started filtering out to the suburbs, it got a whole lot more interesting. "When we did our first major tour, all those kids felt the same as us. And I felt that was the real heart of what punk was about. It was all going on out in the sticks. The whole boredom thing meant more in the suburbs. They couldn't see that in London, with all the stuff that was fucking going on, all the clubs." The Jam were Who-influenced. Burchill and Parsons drove Weller down to Pete Townshend's studio one day, but he wasn't there, although a meeting was later arranged by Melody Maker. In 1995, he recorded a version of The Beatles' "Come Together" for the War Child benefit album, with Paul McCartney. Has he met all his heroes now? "I've met a few. It's enough for me to have their records. Townshend wrote me a good letter once. He said, 'The temple to watch out for is the NME. ' "I still love all those people and I still love what they did. It's just not that important for me to meet them. We're a couple of generations apart. Their attitude and philosophy of making music is very different to mine. I wouldn't want to do a musical [i.e., a la Tommy]. I'm not an all-singing, all-dancing type of guy." Did you agree with the general consensus -that This Is The Modem World was a step sideways? "Yeah. It was rubbish, half of it. There's a lot of real die-hard Jam fans who like that record. It's kind of an elitist thing, because everyone hated it when it came out. It was a bit uninspired." Are there any tracks where you can see your songwriting developing? "No, not really. I haven't heard it for fuckin' years. I remember 'Life From A Window' - that was a good song." Was the cover of "In The Midnight Hour" a nod to your R&B roots? "We were stuck for material more than anything else. That was one of the things we used to play in the live set. I was writing already, before punk, sort of Beatles derivatives, but mainly our set was R&B and rock'n'roll covers. So we'd be doing stuff like 'Midnight Hour' slowed down. Then I saw the Pistols and my life changed, although we still did that hybrid of punk rock and R&B as well as Mod." Sounds a bit like Dr. Feelgood. "Did you ever see 'em? Wilko [Feelgoods' mad axe man] used to jump up and do the splits, and start running backwards and forwards across the stage. Fuckin' brilliant." All Mod Cons was enthusiastically received. Could you feel your songwriting improving? "Yeah, I could. I'd found my feet. Modem World was a low point. You make your first album - basically, it's your live set. It took about 10 days to record. All of a sudden, we'd used our 10 songs and you've been out on the road and you've got to sit down and write another album. Which we did, the same year - and it shows. But it didn't happen. It was . . . what's the word I'm looking for? 'Shit ! It was shit. I had to sit back and going to let this slide or fight back against it?' I had to prove my worth, sort of, 'This is it.'" You had a steady girlfriend - Gill Price -by this point. Was that stability important? "I think it's totally separate." Had you started to move away from the other two in The Jam? "Well, I fell in love. All of a sudden, that person becomes your world, you know, so you don't hang out with your mates any more. [Pause]. But I wouldn't say any of that had a bearing on my work." Did that distance give you the space to create? "Nah. More like, 'Fuck, I'm going to prove myself.'" To critics, to your audience, or just to yourself? A bit of all of that. But to myself, mostly. I've often been good at that, when my back's against the wall. It's like self-pride. A belief that I am still fucking good and I can do it." "English Rose" was the first punk ballad. Quite a brave step? "It was at the time, because we hadn't done anything like that."

How did it go down at gigs?

"We never played it live. I had enough fuckin' trouble recording it-it had quite a few tricky chords. I can actually remember recording it. No drums or bass, just me and an electric guitar. I was very self-conscious singing those kind of open words. It was very revealing. Like bearing your soul a bit." Was that the first time you did that? "Yeah. There were even some seagull noises on it-1 needed something to hide behind." An early glimpse of the solo Paul Weller? "I suppose so." Is it a shock to hear that "version" of yourself 20 years on? "No, not so much a shock because I feel comfortable with that part of me as well. Some of the lyrics make me cringe because they're so youthful. Naive idealism? Yeah, but I can appreciate it. It was that age, written for that moment. That state of mind." "A-bomb In Wardour Street" was pretty apocalyptic. "It was quite a violent time. There were always fights at gigs. You were guaranteed it was going to kick off at the end of the gig. Even walking around London was a violent thing at the time." In December, 1977, Weller was alleged to have glassed a bloke's face in the bar of Leeds' Hilton Hotel. He turned out to be the Australian rugby team's manager. Said team proceeded to beat "seven shades of shit" out of Bruce Foxton: Weller spent the night in the cells. Did you ever get attacked on the street like Johnny Rotten did? "Not so much, but there were times we come close to it. At gigs, beer mugs would come at you -that's if people liked you People would spit on stage and all that bollocks " You didn't like that? "No, I wasn't that keen, really." Did the public think you were more like them than your Strummers and Rottens? "Yeah, and they were right, we were. I think also, by the same token, the press - it was easier for them to get into The Clash because there was an intellectual side, like fuckin' Lenin, or. . . know what I mean" And I could only quote Lennon' "We were the real deal, though, I think. Without hyping it all up, we were three suburban, pretty green, ordinary people." The People's Band? "It was a people's band. I know it's dodgy ground when you say those things because it sounds a bit pretentious, but it's fuckin' true And there was always that feeling at gigs, man. That we weren't all that dissimilar to our audience." You would always talk to your fans, let them come back stage. "It was great at first, because we was popular - we'd started to take off. Then all of a sudden there were 100 people outside after the gig, and then there were 500. I kind of retracted from that point. Put up a wall a little bit It was a bit freaky for me I thought it was kind of a bit odd. We was trying to say, We're the same as you.' But once something blows up big . . . one of my aunty's friends was saying something about how in Hendrix's day they used to speak to people afterwards, but I was saying to her, 'You forget there were only about 60 people at his gigs in them days What about when it's 6,000?' It gets increasingly difficult." Those situations are more controlled now by press officers and minders and record company types "I don't do that, man. Some bands do We never had that stuff." Do you think it's changed over the last 20 years? Can someone just approach you? " It all depends how big the gig is. And how many people come to see us We did the early college gigs when there was a couple of hundred people, and you'd speak to a few of them in a pub afterwards Once you. start playing to thousands of people and there are hundreds of people milling about outside, it becomes physically impossible " Like that Newcastle gig in March, 1982 where you nearly had "the breath sucked out of you" (Our Story Bruce Foxton and Rick Buckler, Penguin) by fans grabbing at your scarf? "That freaked me out - that was the first time thought, I dunno if I like this.' I liked it on one level, but … all of a sudden you get elevated to this other status, which isn't you. Yet the things you're singing about or speaking about are quite the opposite of that." Have you ever waited backstage for a band? "Yeah. I went to see Wings in '73, and waited outside Hammersmith Odeon. Denny Lame spat at us from out of a window." The first punk rocker' "Yeah, probably. C***." SETTING SONS?

"Sound Affects is my favourite, but there's some good songs on Setting Sons. I quite liked the style I wrote in in them days, which was me trying . . . I was trying to write how I spoke, almost like some conversational style, putting stuff in that were just every day images-that was unusual for the time " Were these songs more autobiographical? "No, they weren't about me It was all kinds of external things in them days - a subject or a person. It's pretty different to what I do now, which mainly stems from my own thoughts and feelings." Did you want to write about yourself? "I didn't have fucking much to say. I was only 21. You've got to live a bit first. Also, my whole world was just constantly being on tour or in the studio. So I was just trying to take everyday subjects, and write about things that other people weren't writing about - working-class life or culture." Have you ever been guilty of romanticising the working class, and generalising about class issues? "No, because it's still the middle class in control. There's still a class war." Setting Sons was a concept album, loosely based on three school friends who veer off in three political directions. "Well, it started off like that. I had this idea about these three friends, which in a way was based on me and two of my friends at school who started The Jam off - not Rick and Bruce, two other guys [Steve Brookes and Dave Waller]. There was a concept and I was going to follow the whole thing through, but I gave up after four or five songs." Did that really happen when you were younger, that three of you went three (political) ways? "Yeah. Because we had these teenage ideas, with the band - like, 'We're gonna make it.' Which we did, but it wasn't the same line-up as we started off with. One of the guys [Brookes] left because he was quite disillusioned with it. He went off and did his own thing, and then the other guy, Dave Waller, died of an overdose, from smack. So it was based on us three, but either it was too much hard work or I just lost the plot. I thought I'd just write some songs." Was it your Sgt. Pepper or Ogden's Nut Gone Flake? "Not so much Sgt. Pepper, not conceptual in that way. But with a story running through it. Pepper and Ogden's weren't concepts, they just hung together. Ray Davies tried it on Village Green . . . I'm not sure about concept albums - they just turn 'em into musicals twenty years later. "Eton Rifles" was your biggest hit up to that point. Did it feel momentous? "It did even when I was writing it. I was in a caravan down at Selsey. I went away for a week with me girlfriend. And I knew then it was going to be something special." Did you have the tune in your head? "Yeah. I found that riff on me guitar [hums it]. I just kept singing it into my tape recorder. Crotchets and quavers? I wasn't that sophisticated. I can't write music. I always feel if it's good enough it will come back to you." "Heat Wave" was another LP-closing soul cover. "Yeah, one track short of an album again [laughs] -'Let's fall back on the live set."' Did Bruce Foxton ask if he could write more of his own material? "Not really, no." Was he happy with the amount he contributed in terms of songwriting?

"I don't know if he was happy, you'd have to ask him that. It wasn't like he came with bundles of songs. And I wasn't the kind of person who'd have said, 'No, I'm not doing that.' But from All Mod Cons, as my writing took off more, it was harder for him - there became standards to match, know what I mean?" All Mod Cons was immediately rated the album the other new wavers would have to beat. Charles Shaar Murray in the NME, for example . . . "That two-faced fucker. Then I see that, years later, he was saying I based my whole career on The Small Faces and George Orwell-which is such a fucking stupid thing to say." There are worse people to base a career on. "They're not bad, it's just a load of old bollocks. It's a dumb thing to say. Ridiculous. I never based my career on any one particular thing, man. What annoys me is he [CSM] said it when everyone had the knives out." Back to Setting Sons. "The only thing I wasn't happy with was the sound, but I've never liked that dense, over-dubbed sound, the tracked-up guitars. I like Sound Affects more. That minimalist, stripped-down sound." Prior to the release of Sound Affects, you were listening to Joy Division and Wire, the artier end of punk. "The student side, wasn't it?" Had punk finally lost sight of its original ideals? "What I got from punk was totally different from everyone else. I saw it as a working-class revolution, a cultural thing. Real desperation. It was getting people out of the bedrooms and back to gigs. It was really exciting, Starting a band or doing a fanzine. There'd been nothing around for years. All those crappy Seventies groups. It was exciting to see bands your own age - or pretty much your age. It might not seem that important now but it really was." Punk was egalitarianism in action. The DIY ethic. No longer the special preserve of the uniquely gifted - "Anyone can do it." Do you believe in total freedom for people to make music, without quality control? "That [quality] comes the longer you' re doing it." Given the speed with which bands are expected to come up with the goods these days, would The Jam have been forced to give up after This Is The Modern World if it had been made 20 years later? "Yeah, probably, we'd have been out on our arse. These days, if you don't have a hit single you don't even get to do an album. I guess we were at the end of all that. We still weren't totally in control, but compared to young bands nowadays we were. But if you're any good you'll still come through, you've just got to be really dedicated." Sound Affects, then: stark, angular, brittle . . . "It was more experimental. I've always worked in traditional forms; I ain't got a problem with that, that's the field I work in. I don't think, 'Drop a bit of Captain Beefheart in there for effect.' It ain't me unless it happens naturally. But there were some influences from those bands [Joy Division, Wire]. The Slits as well." How were you feeling at the time? "I was constantly stressed, to be honest. I'm a natural writer but though it comes easy, you've still got to work at it. So there was always that deadline: I've got to make the album by this time.' Much more so in them days. I was always under pressure, and I really didn't feel like I had much support from the other two [Foxton and Buckler], either, when the chips were down." The albums came pretty thick and fast, but you released a lot of singles in quick succession as well. "And singles could last 18 months in the charts back then. Now they last two weeks, if you're lucky. It was a great time for singles. All these kids would be going out '- the shops would be jammed. By the same token, it puts you off - why put that energy into it? Nowadays, singles are just an advert for the album." One of the songs from Sound Affects, "That's Entertainment", became a hit single purely on import sales. Was that your "Smells Like Teen Spirit", your sardonic indictment of popular culture and the leisure industry?

"It was more about everyday things as entertainment, a pop arty idea." Are you down on superficial pleasures? "I veg out in front of the TV from time to time. I never used to watch a programme or read a book unless I was gonna learn something. But it's always been crap. It's the same as TV stations in the States. There's hundreds of them but they're all shit. No, I haven't got cable." Did you feel like you were taking a stand against all the crap? "Yeah. I always felt we were better than everybody else" Better than Magazine, PiL, Gang Of Four, Joy Division ? "Yeah. I don't know, it's some kind of arrogance." At each point, did you feel pleased with the response you got from audiences and critics ? People were waiting. 'What's the next one?' They were exciting times. That was my favourite year, '80. We were pretty big, but we were still doin' three or four thousand people gigs. The Clash famously refused to go on Top Of The Pops, but you were regulars. All those years we sat indoors every Thursday watching it. It was an achievement to get on there. Were you still excited about chart positions? "Yeah." "Going Underground", your first Number One, was left off Sound Affects. "You couldn't do that now. Like I said - singles were more important then. It's a shame because it's like a death of that form. It's fuckin' awful - and the whole thing with the Internet. I can see it gets rid of the record companies, the middle men, but it's not the same as a kid going out and buying the record." Weller has been accused of plagiarism. "Amongst Butterflies" (from Paul Weller) has a louche. Sly Stone-circa-Fresh feel, "Mermaids" (from Heavy Soul) is reminiscent of The La's' "There She Goes", while the latest single, "Brand New Start", is based around a similar chord progression to John Lennon's "Jealous Guy". He is unfazed by my connect-the-dots routine, just as he is when reminded of the brickbats hurled at him for his most notorious trip back to the Sixties-"Start!" "It was obvious, wasn't it? The only thing I can say in my defence is that the tune ain't [from The Beatles' Taxman']. We just took the bass and drums and the little guitar bit. I think we copied James Brown myself." Did George Harrison call? "Nah. He's in no position to talk, is he...?" Did you lose that sense of longing for the city once you started living there? "I'd been in London quite a long time by then. moved to London in 1977." But did you still feel like a kid from the sticks, dreaming of the city? "I still felt like an outsider." Is it important to be outside a city to retain that sense if awe? (One wonders where Ray Davies, the Muswell hillbilly, was living when he wrote "Waterloo Sunset".) "Yeah, I suppose so. I loved it at first. I lived in Baker Street, then I moved to Victoria, then Pimlico. Maybe it's because I came from outside London, but when I lived in Pimlico, which was quite near the embankment, I just enjoyed walking along the streets. like seeing city sunsets. "Coming here today, I was walking along and I just started singing 'Waterloo Sunset'. I remember coming up here as a kid, it was a big deal-seeing Cleopatra's Needle or Nelson's Column. To actually be among it was fantastic." I ask Weller later if he considers himself to be "quintessentially English".

"Those are media terms," he replies. "I'm English because I was born here. I'm not a little Englander." Did The Jam attract the wrong element because of a perceived thoroughbred Englishness? "I wouldn't say so. There were maybe a few Union Jacks around in 1979." To what extent did you indulge yourself in The Jam days? "What do you mean? In terms of ego?" Spending money. "I was never like that. Which used to lead to accusations of me being mean, but I was just against it. I was very suspicious of it - all the trappings of success. A very serious young man." Where did that come from? You went from being a happy, carefree kid to a young man with the weight of the world on his shoulders. "I was on a mission. Soon as I got into the band, that was it. There was nothing else in the world apart from playing music and trying to make it. I'm still like that." Did the punk and post-punk bands hang around together? "Not really, no." I can imagine Weller being mates with Kevin Rowland. All that Projected Passion and Intense Emotion. "He used to be in a band [pre-Dexys Midnight Runners] called The Killjoys. They had a girl bass player, and another girl used to come and touch up her tits while the band played 'Great Balls Of Fire' or something. It was different, I suppose ...I met The Police at some French festival. They were a four-piece at the time. One of them lay on the floor while the guitarist gave him a good kicking. There was a lot of bollocks in punk-all that posing." Did you check out many of your peers? "I liked The Clash in the early days, all those paint stained clothes. I couldn't understand it [Situationist slogans, etc.], but I liked the look. Joe Strummer saw the Mod in me. He's the first one who had me sussed. "I didn't understand The Damned, because they were so much older than me. A lot of those bands, like The Stranglers, had been on the pub circuit for years; suddenly, within a few months, they've got short hair and they're wearing skinny ties. "Same with Jimmy Pursey - he was much older. I've probably always taken things too seriously. I was, like, 'Man, it's a revolution, not all these imposters.' They were probably only 22, but when you're 17/18, they're fuckin' hippies." In the Seventies, I recall Weller decrying the "old men" -that is, over-25-year-olds -still in the rock game. Then 30 became the dreaded age. Now he's 40. . . "I thought my life would be over by my 21st birthday. Then 25 became a watershed." It occurred later on that, of all his incarnations, it was probably The Style Council who offered the most dignified way to carry on into middle-age: less about "doing it live", allowing for a sedate existence in the studio. . . Will he still be rocking at 50? "Sitting here as a 40-year-old, I can't imagine it." Were you a fan of Elvis Costello? "Not at all." How about the CBGBs crowd? "I never liked any of that American stuff. Like Television. I remember going out and buying those records because there were no punk albums at that point, but I couldn't listen to them. They did nothing for me. I liked lggy Pop because he was a personality, but I didn't like The New York Dolls or any of that bollocks." The gap between albums five and six (The Gift) was The Jam's longest yet. "We got into this thing where the album came out every November, so it was a way of getting out of that."

Weller obviously clocked the drift among post-punkers away from rock towards funk and soul. In 1981, bands like Stimulin, Funkapolitan, ABC and Spandau Ballet explored the potential of black dance rhythms, while Britfunk outfits such as Freeez, Beggar & Co., and the criminally overlooked Central Line (whose bassist, Camille Hinds, now plays with Weller) briefly gave American R&B acts a run for their money. "We got into soul again. We started backtracking. I was into soul as a kid. I was on a big learning curve." The Gift was The Jam's most stylistically varied album. There's calypso on "Circus", and "Precious" evinced Weller's fondness for Pigbag's "Papa's Got A Brand New Pigbag". "Yeah, I nicked that." And "Town Called Malice" was the Motown tribute. "It went beyond being a pastiche. I really liked that energy. Everything's written in a certain time, a certain state of mind. 'Clutching empty milk bottles to our hearts'-that's still a great line." Were you as pleased with The Gift as you were with previous albums? "Most of it was fucking good." But could you feel the band winding down? "The band was winding down. I'd had enough of it all. I really wanted to move on and do something else. I couldn't get any further, musically, with them [Foxton and Buckler]. I thought, 'This is a good point to stop and try and do something else.' I just couldn't see myself being in the same band for 20 years." Can you now hear yourselves falling apart on The Gift" "Nah. I can't hear that on any of those tracks. I like "Just Who Is The Five O'clock Hero?', 'Ghosts', 'Carnation' - there's some great lines on that. It was just that I'd have enough." When you were in Italy with Gill that summer, did you realise you didn't want to go back to The Jam?

"It wasn't like that at all. It was the first time I'd ever been on holiday. If you lounge around in the sun for six months you come back and see things differently. I just thought, I don't want to be doing this for the next 10 years.' I've got respect and admiration for bands like the Stones. It's tough keeping a band together. But it wasn't for me." When you told Bruce and Rick, could you see their jaws drop? "It didn't go down well at all, mate. The gravy train had pulled into the station." Did you have any second thoughts? "No. Not at all." Any doubts? "Oh, yeah, 'course I had my doubts. All the security and structure we had around us. I thought, 'Am I really going to take this chance? It might happen or I might lose it all.' But I thought, 'Fuck it.'" Why wasn't "The Bitterest Pill" on The Gift? "It was a bit cheesy, really - rather like a swansong. I was trying to write a modern classic ballad. But no, the song wasn't anything to do with the band." What was the mood in the band like by the end? "The ironic thing was, on that last tour we did-'82, I suppose it must have been -we got a really good vibe. We were playing loads of old songs like In The City'. It was probably because the pressure was off me." You knew you were moving on . . . "Yeah." Did you decide in Italy?

"Yeah, but I was still bound up in the whole Mod thing. The roots of it. It really caught my imagination. I suppose I started listening to jazz as well. Different influences, anyway." Jazz was in the air. Clubs like The Wag and Le Beat Route were going through their Absolute Beginners phase, there were outfits like Sade, Working Week and Animal Nightlife with their be hop, cool jazz, torch muzak and lounge pop . . . "You've got to laugh, man, because I've been around such a long time, I've seen so many movements come and go. But I always seem to be part of them somehow - not in my mind, though, not intentionally." You inadvertently "do a Bowie"; anticipate changes? "No, not at all. Apart from the press making it up. There was that cod-jazz thing, Working Week and all that, there was fuckin' punk, new wave, power pop, the Mod revival - I've always been part of it somehow."

Happy Together: The Style Council With the exception of The Beatles, no one had ever broken up such a successful band before. "By the same token, it wouldn't have made any sense to split The Jam and form another power trio." With The Sex Pistols' reunion last year, regular gigs from the likes of The Damned and Siouxsie & The Banshees, and even Bauhaus on the comeback trail, that leaves just you and The Clash. "I find it a bit sad, really. If you've got any sort of talent, shouldn't you be able to create something new? I've got a lot of time for Paul Cook and Steve Jones [of the Pistols], so I guess I'd say good luck to them. But then, they're one of the few bands who could say, 'We're just doing it for the money.' That becomes a statement in itself. But I wouldn't like to get to that stage. I'd much rather play boozers and make a living like that." And so to The Style Council. "The Difficult Years." You could almost hear you sighing with relief as soon as "Speak Like A Child" came on the radio.

"I just had so much fun-especially my first couple of years. Good memories. To be 21-22, as I was with The Jam towards the end, and to be that pressurised, it wasn't particularly enjoyable, although I have fond memories. But it was fucking hell. I'm on the road half the time, then I'm in the studio. I didn't have a great deal of time to enjoy it. You've got to get your head down and work, work, work: that's what you've got to do to be successful. But with the Council the weight was off me. I thought, I'm just going to enjoy this.' I still wanted to work on my music, obviously, but there wasn't that pressure. "In the first year of The Style Council we didn't make an album, we just did four singles and waited for the album to come along. It was just me and Mick [Talbot] - and all the time we worked with different people and different line-ups." British Electric Foundation, Public Image Limited, Leisure Process International, even The Chic Organisation - there was quite a lot of talk from The Style Council's predecessors and peers about The Death Of The Rock Band, and its replacement: the pop group as sleek, modern corporation, out maneuvering the music business, within whose structure the "star", surrounded by like-minded associates, could recede into anonymity. Did you want to get away from being a public person with The Style Council? "Well, there was that, but I also wanted to experiment musically." "Speak Like A Child" was a radical departure. Did you get legions of pissed-off Jam fans moaning at you? "More with 'Money-Go-Round' [the second single]. We bumped into a bunch of Mod kids in Carnaby Street and they were saying, 'What's all this jazz shit?'" Did they take your "defection" personally? "Some did. I was less concerned - despite the name - with what style the band was about overall. I just wanted to treat every song individually." An anything-is-possible approach? "Yeah. I mean, we did a lot of shit, but there were some great songs. There was something lacking. . ." Were you as committed to The Style Council as you were to The Jam?

"I was totally committed to The Style Council. I was totally obsessed with it. Before, The Jam had been my life. With The Style Council, maybe there was a lack of confidence. I don't know what it was. I found it difficult to get to grips with what was in my head. My voice sounds a bit whiney." Weller was in good spirits by this stage. His reported breakdown in January, 1982 (fuelled by huge quantities of booze and exacerbated by a rigorous schedule) was just a bad memory. Did he ever go off the rails with The Style Council? "I've always gone off the rails. Now and again. But I always get back on." Has he ever had a fully-fledged mental collapse, a real screaming-abdabs roller-coaster ride to hell, a Brian Wilson-circa-'64job? "Nah. I had this really bad time when I was a kid, about 16. I was sitting on a train with my friend and we dropped half a tab each - they must have been quite strong, microdots as they were then. We'd been laughing hysterically for hours and hours and hours on end and we got back on this train, and all of a sudden there was this siren and I just ran screaming off the train." The Style Council were less "rock" than The Jam-but in every sense? Did you indulge in rock star excess? "Give me an example. Drinking?" Shagging. "No. I fuckin' should have done. That's the time to do it, really." Weller does remember one incident where he did avail himself of the facilities, so to speak, when he disappeared into a toilet with a young lady after a gig, only to reappear a while later with a smile on his face. But he doesn't like the term ''groupies". "I don't like to call it that. There's a man and a woman . . . it was fuckin' great. It's what makes the world go around. "With The Jam, my first girlfriend [Gill] used to come with me most of the time. I was just too young, looking back on it. With the Council, I don't know -I really wasn't into those rock'n'roll accessories." "Anti-rockist" was a popular buzz-phrase. Were you really down on rock?

"A lot of my attitude was based on Mod. I was never into rock bands. We were more purist - I was totally into black music. I was so puritanical about it that you cut your nose off to spite your face." How do you rate the council's first album, Café Bleu? "Our production makes it sound dated but I was pleased with it. They're just good songs, kind of me finding my feet as a writer. They're not necessarily social commentary - we weren't part of a movement or generation, and writing from that point of view. We were just trying to write a song." In a way, The Style Council were as hip to their audience as were The Jam - 25-year-old suburban soul-boys high on fashion and 12-inch dance imports. Were you still speaking directly to your disaffected suburbanite audience? "Maybe. There were ex-Jam fans going to clubs or getting into jazz-funk. There was a 'casual' thing going on -we had quite a lot of those types of kids turning up at the early Style Council gigs." "Dropping Bombs On The White House" is suddenly, in 1998, topical, but it was recorded towards the end of the Cold War. "We wanted to call the album that in the States and they wouldn't let us. All those nuclear warheads sitting in our country. It was a dodgy time." "Long Hot Summer" (their biggest hit, not included on Cafe Bleu), "You're The Best Thing", "The Paris Match": were you feeling more comfortable singing love songs? "Yeah, because I wasn't singing to anyone in particular." What about your much-lauded "gay phase" on the video for "Long Hot Summer", all that flirting with Another Country chic (later made explicit on the cover to Our Favourite Shop), and you and Talbot playing with each other's ear-lobes? "The record company was really unhappy about that video - the MD was complaining there were no women in it. So for the next single we did a special edited version with bits from a porno film, loads of shagging an' that - I think he [Polydor's MD] liked that one."

If The Jam were dour, The Style Council were playful: the sleevenotes attributed to latter-day dandy The Cappuccino Kid (contemporaneous to Paul Morley's stratospherically high-falutin' mini-essays for ZTT), the references to 18th century French philosophers, the sartorial and tonsorial experiments . . . "There were lots of wind-ups with The Style Council. Again, we cut off our noses . . ." With The Jam, you were possibly the least androgynous pop star ever. Then, suddenly, you're dyeing your hair, wearing make-up and Francophile haute couture. What was that all about? "I was confused." Sexually? "A little bit [pause]. But not to the extent that I like it up the arse." I picked Weller up on this intriguing remark the following afternoon, down at Black Barn studios near Woking. Did you mean it when you said you dabbled . . .? "No," he admonished, aggrieved at my intrusive line of enquiry. "I didn't say that. You're fuckin' putting words in my mouth. It was a wind-up. Don't stoop to a tabloid mentality." The subject of the tabloids cropped up again later that day, during a chat about Bill Clinton. This time, Weller was less stern. "He [Clinton] smoked pot and never took it down; he had a blow job but didn't come. He's got a problem with inhalation and exhalation! He wants to be careful he doesn't blow up. Either have a blow job or don't. If you're not going to smoke it, pass it on." Zippergate raises serious questions regarding the matter of public duty and private life. "At the end of the day, I'm not interested in who he's shagging as long as he's doing his job properly. You know where it's stemmed from - the fuckin' Republicans wanted to stitch him up. It's not about a blow job, it's about trying to bring him down. I mean, is the man doing his job? That's what matters. It's judging a man by his private life."

Returning to Weller's own private life, I asked whether he'd ever had a crush on a bloke. "No. I like crumpet. That's what I like." Mick Talbot not your type, then? "Nah, mate. Too burly." This seemed like the appropriate moment to prod him about his status as role model for Generation Loaded ("Where does that come from? I've never understood that"), and to discover his tastes with regard to the fairer sex. Given the choice: Polly Harvey or Melinda Messenger? Weller looked as though he'd been asked to decide between pig's blood and pickled onions. "Polly Harvey, I suppose. At least she's got something to say for herself" Our Favourite Shop , was your first Number One album since The Gift. Did you feel like you'd gelled? "Yeah. It was a very cohesive album. The best thing we did, overall, track by track." Politics and pop made uneasy bedfellows at the time. "That was the time of, 'Get on your bike and go out to work.' Norman Tebbit. All those fuckers. Whole communities destroyed." Did you ever have any doubts about the pop song being the correct platform for addressing such issues? "Well, that was the form I worked in. I just thought, 'Whatever I do, I have to try and make a difference.'" Were you disappointed by the effect the music had? After all, Thatcher prevailed . . . "It didn't wind me up that far. I just think each person has to do what they can." Did you expect "Walls Come Tumbling Down" to have a giant impact? "Not enough to think it would bring down the government. Just to open eyes. 'You don't have to take that crap. 'That line was about Frankie Goes To Hollywood, and all those crappy fuckin' bands who were like the pop aristocracy, with their suits and pearls." Did you really hate the Eighties groups that much? "Not with a passion. At the time, I thought it was quite - not debauched, just fairly indulgent. Again, I was just so fuckin' serious about everything. I thought everyone should try to make a difference, be concerned about what's going on in this country. " You liked Spandau Ballet's "Chant No I" and some of the Orange Juice singles. "They were all good writers, but it just wasn't my kind of music." Paddy McAloon, Roddy Frame and the new wave of "classic pop" auteurs? "Voices are a personal thing. You like them or you don't. It's difficult once you've heard Aretha Franklin or Al Green -you judge everything by that standard. "To me, that Eighties stuff has dated much quicker [than Seventies music]. It was all the same digitised sound, with few jagged edges." All the rock bands of the day were railing against the Tories, and yet, ironically, punk happened during a Labour government. "Thatcher was different, a different form of politics, much more tyrannical. I think she should have been lined up against a wall and shot, personally." In January, 1986, a coalition of Left-wing acts - The Style Council, Billy Bragg, Junior and The Communards - undertook the Red Wedge tour, designed to encourage Britain's young to vote Labour. Photo opportunities with Neil Kinnock and Ken Livingstone ensued. You felt an obligation to stand up and be counted with Red Wedge? "Yeah, I did. I did regret it, though. I was watching that thing about Creation [last month's Omnibus special, 'The Man Who Discovered Oasis']. Tony Blair, I mean-they're more showbiz than we fuckin' are." Power crazy? "Up to a point, yeah."

Did you ever abuse your position? "I don't know. People just start acting like complete c***s sometimes." Any examples? "No. Just being thoroughly fuckin' horrible to people.' But you 're proud of Our Favourite Shop? "It's difficult listening to it. It's like going through old photographs. Do I get nostalgic? Yeah, but I'm happier now. I've always been more caught up in the now-despite accusations about being retro. I'm more concerned with what I'm writing right now." Lenny Henry featured on "The Stand-Up Comic's Instructions". Were you a fan? "Not really. I like humour with pathos. Like Steptoe And Son, Only Fools And Horses. I really like Chris Morris as well." Any of the American shows? Seinfeid, The Larry Sanders Show ? "A lot of their humour I don't understand." Andrew Dice Clay, Sam Kinnison? "Is he that geezer that got killed in a car crash? Yeah, he was funny. Who's the other guy? Denis Leary? He's all right for stand-up." You have been accused of having no sense of humour. "That's fair enough. I've mentioned two or three times how serious I am. When it comes to the music, I am. I don't want to give the Impression it's all miserable. But all my friends say I'm a rude, miserable bastard. They can't all be wrong." The Cost Of Loving was your least successful record to date. Were you losing interest? "I think we became out-dated - an anachronism." There was a shift in interest away from "New Pop", with its jazz, funk and soul inflections, back towards rock, with groups like The Smiths and R.E.M. "In '86, I saw The Smiths at Newcastle, and the power . . . as soon as they went onstage, it was like The Jam, really. You didn't get that with The Style Council at all." Did The Smiths attract all those dispossessed Jam o fans ? Did you want to draw them back? "No, we were still on course. But, objectively, I could see - 'That's fuckin' exciting.' By that time, it [The Style Council] didn't have that same fire." The Style Council were no longer as attuned to the British Zeitgeist as before, there was some convergence with American dance music-Jam & Lewis' work with Janet Jackson and Alexander O'Neal, for example, tracks like Dennis Edwards' "Don't Look Any Further" (sampled by Eric B & Rakim for "Paid In Full"), even Luther Vandross. "The Cost Of Loving" came more from what you'd call modern soul. That's what influenced us - underground music. It was done well, but there wasn't enough passion in the performances to pull it off. And the songs weren't up to scratch. In the last few years, I haven't had to think about it so much. At that time I used to go through so many tribulations about what I should be singing - I could always hear what it should be like, but I couldn't transfer it physically." How about that orange sleeve - a citric version of The Beatles' White Album ? "The only thing I can say in its defence is that it's in some book as one of the top 100 album sleeves" Uncut's favourite is next: Confessions Of A Pop Group. Half of it features sublime instrumental passages worthy of Satie, Bacharach or French soundtrack composer Francis Lai; the other half is consummate white funk. The album, with its tripartite suites and vaulting ambition (a problem, ironically, for the very same people who had previously dismissed Weller's compositions as simplistic and ordinary), drew venom from many critics while the public were largely unimpressed For this writer, Confessions … provides the most credible, and most compelling, depiction of "the real Paul Weller" : the sentimental, wistful romantic luxuriating in European melancholy (strings, piano, synths); the suburban soulboy in love with modern America. The crowd. applause during "Confessions 1,2,3" is especially poignant, considering the speed with which the Council's fans were deserting them.. Why so sad, Paul? "I've always been drawn to melancholy things. But it wasn't for any particular reason. It was quite a happy time. Dee (C. Lee, ex-wife) was having my first child. I am drawn to those types of sounds, especially Marvin Gaye. But I wouldn't like to be miserable and sad just for the sake of it. You've said you were reluctant to draw on your own experiences before this, but surely here you veered more towards autobiography? "It wasn't as literal as that. It was just a mood. Not the result of any particular event. I'm always trying to write a good song, and If it's just about one experience, that's just fuckin' boring. "As I told you, my young years were all work, work, work. That's an experience in itself, but it's not the sort of experience songs are made of. You couldn't write a whole album about being on the road, or being in a hotel room. "But I thought it was really good. There was a little Beach Boys tribute at the end of the first side [the coda to 'The Gardener Of Eden']. I think whatever I'd have written or done at the time, it would have been out of touch. But I still stand by that record." Talking of The Beach Boys - these were your Carl And The Passions : So Tough (obscure BBs LP from 1972) years, when you were either ignored or misunderstood and maligned. But the music - ornate opulent, overblown - was arguably a truer representation of what you were about than ever. "I like to think all of my albums are a true representation of me. Even if you don't like the whole of it there will always be one or two great songs." So "The Gardener Of Eden" is as much "you" as, say, "Beat Surrender'"? "Yeah." Confessions . . . got mixed reviews, from the lukewarm to the savage. Were you disappointed ? "I must have been. I put a lot of time into it, and there was a better vibe when we recorded it than The Cost Of Loving, which was a real rough time for us. It wasn't particularly inspiring and I felt we'd got back on track. I thought, lyrically, the songs were really good. Again, some of the performances were lacking." What led you to write such a desolate, haunting piece of music as "It's A Very Deep Sea'"? "It was Just me sitting down at a piano and hearing that first chord, and just what that inspires. It sounds like you're just sinking into the depths." Modernism: A New Decade (The Style Council's "house" album) was rejected by Polydor in 1989, and has only just seen the light of day, as part of the five-CD Complete Adventures Of The Style Council. Did you get into acid house ? Ever go down to Shoom (legendary club run by Danny Rampling)? "I wasn't really big on it. I liked the East Coast, New Jersey stuff, more. That band, Blaze, I really liked. For the first time in a long time, I could hear the gospel influence, and it was still pretty much underground." Weirdly, the nascent Detroit and Chicago dance scenes were influenced by the UK electro-pop of Depeche Mode, Soft Cell, The Human League and Yazoo. "Juan Atkins [Detroit techno pioneer] did some remixes for us. They were fuckin' awful. I think what we were doing ourselves was better." Did you get into Ecstasy ? "Not very much - I was anti- all that. I got into it later, but not in a big way I found it very liberating, dropping E. But then that sort of wears off after a while. A lot of those superficial highs, they're exciting at first, then they become boring or ordinary." Have you ever gone onstage high or pissed ?

"No I used to [with The Jam]. In the Council days I was happier." How pleased were you with Modernism. . ." "I wasn't jumping around the room, which I think is probably a bad sign, but I liked it." Were you gobsmacked when Polydor rejected it" "Yeah. I've made all you fuckers millions of pounds. At the same time, it taught me a good lesson." Weller was a record company boss himself when he ran the Respond label (which folded in 1986). Surely if Respond had lasted, there would have come a time when he would have had to reject a below - par record. "I probably would have. Unfortunately. I'd look after people though, know what I mean ? Just because you don't like what someone's doing, it doesn't mean it shouldn't come out. You're right, though - from a commercial point of view." Nineteen - eighty - nine was an in - between year, just after the Second Summer Of Love, but before Madchester. Were you waiting for something to happen ? "I was waiting - not externally, just inside me. 'Where do I go from here"' We'd kind of made up our minds before that to finish it." Like Bowie. . .

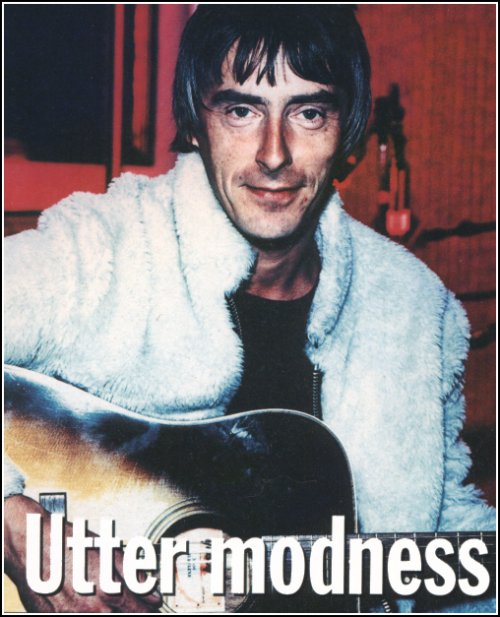

"You keep mentioning him." . . . you were going to have to change direction again Brand New Start: Paul Weller The solo years are subject to Paul Weller's scrutiny the following day, when Uncut meets him down at Black Barn, the studio he uses in Ripley, near his Woking home (a modest place offset by a swimming pool with a Mod target at the bottom). Inside the studio, where he is working on a track for acid jazzer Matt Deighton (Ex-Mother Earth and guitarist with Weller's band), it is humid and quite warm. Uncut photographer Tom Sheehan - a man with a cockney accent so broad he makes Weller sound Rupert Everett - shoots quickly ("I look like I Gushing," he says when he sees Sheehan's Polaroids) so that the interview can recommence. Outside in the courtyard, it is sunny and bright Weller - dressed more informally, though no less Mod than yesterday in blue jeans and blue T-shirt- picks the story after the demise of The Style Council. "I started back on the road in about 1990," he says, Bensons and red wine at the ready, "and then it was pretty much solid touring for two years after that." How did it go ? "Some of those early gigs were awful." Reports indicated as few as 200 people at some venues. Was it that bad ? "Yeah, in some places. Again, being dropped by Polydor taught me a lesson It was a grounding thing But it was still a bit depressing. I wasn't ready and the band weren't ready " From the three-member Jam, down to two with the Council, then just him. Weller jokes that his next incarnation will consist of an empty stage and a microphone But how did it feel to be alone for the first time in his career" "It wasn't until the first solo album that I felt back on track I wasn't interested in doing anything for a while. I wasn't really writing, as I remember. Nothing really moved me or excited me to say something." Did you toy with the idea of giving up ? "I did before that. I was thinking, 'What else could I do in life"' I was mainly spending time with my son, because he was born around that time. But it was still frustrating because I wasn't doing anything I liked So I got back into writing songs, at home with a guitar and piano It was nice to write a song from top to bottom - you know, acoustic Something I hadn't done for a long time. And then things started to form in my mind and it got clearer, the more I saw what I should be doing or what I wanted to do."

Because of your then-recent experiences, were they angry songs ? No, quite the opposite. Most of the stuff I wrote appeared on the first album {Paul Weller], which is quite mellow if anything." A couple of the tracks had that mellifluous Style Council feel to them "Yeah, 'Round And Round' And 'Remember How We Started', that's got that kind of jazz-funk feel to it "I was really pleased with that record. I really like the sound. Even though now I feel I'd do some things differently, like sing them better, there's some things which are really special to me, like 'Clues'. "My aim, as ever, was to write songs that move people. I'm loath to say they're about me because it just wouldn't be true." Were you nervous about starting over ? "To some extent, but there was a certain amount of satisfaction because we self financed it {Paul Weller] We didn't have a deal, then we got one with a Japanese company [Pony Canyon], which was a real lifeline. It came out in Japan first, and the money we got with that gave us the chance to finish it. Then we got a deal with Go' Discs." Did you expect "Into Tomorrow" (debut solo single, credited to The Paul Weller Movement - reached Number 36 in March, 1991) to be a hit? "I don't know if I had any preconceptions I don't think I expected it to be a big hit. I was Just pleased that I'd made a complete album. The last few years with Polydor were just a pain in the arse, from the music to the artwork, so it was nice not to have that bullshit."

Paul Weller was your first Top 10 album for five years. "Was it? I'm very pleased about that. Now that I know." The naturalistic, stripped-down approach of solo Weller predated the Back To Basics aesthetic of Oasis et al. Have people credited you with giving them the confidence to move in that direction ? "Noel [Gallagher] is always citing Into Tomorrow' [he quite liked Weller's first band as well 'The Jam were my Beatles,' he wrote in the foreword to the revised edition of Paolo Hewitt's A Beat Concerto]. "He came to one of our early gigs in Manchester, and he said when he heard that song. ... I ain't claiming anything here - that would be too poncey - but I think there was something in there that said to people, 'Ah, that's what live music sounds like'. That whole process of digital recording in the Eighties, it ended up that everyone was using the same equipment, the same decks and stuff- and they all started to sound like everybody else, whether it was rock, dance or whatever" Some people believe music should get bigger and more lavish as it progresses. You went in the opposite direction: lo-fi. "Definitely, with some of that attitude in it. I wanted to make records rougher A lot of people, the longer they go on, the smoother and blander they become I'm always determined to make my records more raw, rougher. 'Peacock Suit' [from Heavy Soul] is one of the best records I've ever done There are very few records that sound like that." Weller seems to have more in common with Nineties acts - Robbie Williams excepted ("A fuckin' joke," he will never later. "We did a festival with him recently and it was like cabaret"). "Music is definitely better now. It seems to have more of an individual spirit, and there's a feeling that bands want to do it. Especially bands like The Charlatans. Whatever shortcomings they may have, they make up for in spirit." Is it like having a second childhood? "I wouldn't regard it as a second childhood, it's just rejuvenating in some ways. The funny thing is, I've got more in common with bands these days, even though they're about 10 years younger than me - with the exception of Bobby Gillespie [laughs]." So you don't think this is a low-point for British music? "I never considered the question. What do you expect a rock band to do?" Be more experimental, less bound to the Sixties. "What about Elastica? Or Radiohead? Or The Verve? If you were 16, you'd have a different point of view. It's very hard to do guitars/bass/drums differently, to be experimental for the sake of it. To expect something startling and new and fresh is a bit much, really." But isn't that important?

"Yeah, but you've got to appreciate the new bands coming up. They've got their own attitude. It may be a low point at the moment because bands aren't selling that many records, but I've seen it come and go so many times. It goes in cycles. In '93, '94, '95, it [Britpop] was all happening. But there's always a comedown. You take it so far, and there's nowhere else to go. I still believe it will come round." The current trend, though, is geezers with guitars. "What about the hip hoppers? Geezers walking up and down the stage with their friends." If The Jam had formed in 1994 instead of 1974, with a mod(ernist) like Weller at the helm, would they have sounded quite different (influenced by, say, Aphex Twin, Goldie, Tricky)? "I very much doubt it. It might be a bit more R&B, or something." One accusation levelled at his solo work is that it betrays a preoccupation with authenticity. "Something real to me, " he sings on "Brand New Start". Or "/ have no pretence" (from Heavy Soul's "Science"). Is he, like the Manic Street Preachers ("4 Real") and the hip hoppers ("keepin' it real"), obsessed with what's "authentic"? Do "truth", "honesty", "conviction" matter? "Something in the sound or the music has to be real enough to connect. You don't have to bare your soul to make it real. I only play guitar because that's the instrument I chose when I was a kid. And I'm only talking for myself that I like it to be real. When you perform, you're always looking for that one point in the song where it all connects." Do Bob Dylan and Neil Young offer a more authentic account of, say, hope, despair, pain, longing and so on, than a Marvin or a Smokey? "No, that's bollocks. That's a white thing to say." Weller has been held responsible for exerting a pernicious influence on today's scene/sound. In his review of last year's Jam box set, NME editor Steve Sutherland blamed him for (what he perceived to be) the current, terrible state of popular music. Along with Noel Gallagher and Alan McGee, some say he's one of the unholy trinity of retro-rock. (for the record, the day before, Weller told me, "There are worse things to be called than 'Dadrock'," especially since, as we both agreed, most dads have cooler record collections than their kids these days).

"I don't know," he says, and if he sounds prickly it is tempered by a reluctance to be drawn into another slanging match about the press. "I never confess to pushing back the barriers of popular music. I'm just happy doing what I do. "Anyway, what grounds has he [Sutherland] got to talk? He's a c***. Allan Jones is a c*** as well." Have you ever been deflected by criticism, or encouraged to change course by something a journalist has written? "No. I don't say I wouldn't agree with some criticism." You've had a fair degree of favourable press of late. "You're joking, aren't you? I can't remember the last record they liked. Even if they like something, it always seems begrudging." You do have your champions. "I ain't noticed." As you said, though, you've never been pushed off course, have you? "I don't make records for the fuckin' critics. They don't go out and buy a record over the counter." I was quite surprised by the message on the inner sleeve of Heavy Soul: "To all my people, you know & so do I. To anyone whosoever slated me - fuck you." It seemed a little mean-spirited considering a) the success he has enjoyed with The Jam, The Style Council and now as a solo artist, and b) the tremendous amount of praise he's had over the years - Modfather this, Godfather of Britpop that, Greatest Songwriter Of The Post-Punk Era the other. But then, what bugs him isn't the ratio of good to bad articles, rather the snidey, often personal nature of the attacks ("Weller wears shoes without socks and jumpers without a shirt, the uniform of ice-cream operators" - The Times)', the sheer invasiveness, particularly of the tabloids ("Standing on the doorstep of your wife and children's house," he tuts. "It's not on, is it?"); and the fact that said articles are, by definition, cowardly - written by yellow-bellied hacks from behind the safety of their word processors. In 22 years, no one - not one single music writer - has had the balls to diss him to his face. "Surely there must be some level. To be called a c*** - I think that's going too far. It's a personal insult." Weller has taken matters into his own hands on more than one occasion. A review of Heavy Soul by Stuart Bailie in the NME concluded that the album was written out of "obligation rather than inspiration" - a contractual effort. He immediately rang the journalist at home. Bailie remembers the phone call well. "His first words were, 'You fucking c***, you need a fucking slapping.' I said, 'Who's this?' He said, It's Paul fucking Weller.' I thought it was a joke. He sounded tired and emotional. He went straight into, 'We're going to have a fight - where are we going to have it?' I said, 'It's a bit tricky-I live in Belfast.' He said, 'Well, I live in Woking, so fucking what?' He asked me how many times I'd listened to the album before I reviewed it. I said, 'Nine or 10.' He said that wasn't enough. Then he told me his words meant more than mine ever will." Again, it wasn't the criticism, it was what Weller regarded as cowardice that so offended and enraged him. You've been called many things: belligerent, vengeful, over-determined, latent macho-aggressive . . . which apply? "All of them," he says, only too happy to receive criticism, as long as he's there to respond. "That's not necessarily a good thing, but that's what it is. I can see them all in myself. I could also add half a dozen words that are positive and good, and they're like me as well." Most rock magazine articles read as though they've been written by the artist's press officer, so fawning are they. Shouldn't there be a more frictional relationship between musician and music writer? "But when it gets really personal, I think it's wrong. If someone doesn't like your record, fair enough - but they go too far. "Steven Wells [of NME] called my audience either cokeheads or dickheads. That's a real insult."

Can white men sing the blues? "Yeah. As long as you're respectful and see where it's coming from. Like Eric Clapton didn't help matters much [reference to Clapton condoning Enoch Powell's infamous 'Rivers Of Blood' speech]. Fuckin' outrageous. Especially when you think black music, black culture, has given that man so much." What gets you angry these days'? "Injustice." Can you be more specific ? "People being trampled on, war, Bosnia, the Sudan. Seeing kids sleeping on our streets, in frightening numbers." Is it worse now ? "Oh, yeah, although probably not compared to Charles Dickens' times." Do you see things improving? "Certainly. I'm not under any misconceptions. I do think attitudes have got better. Nevertheless, all the power and machinery are still in the same hands " Have you given up addressing such matters in your lyrics'? "I don't know how to any more, because if I did, it would Just be me repeating what I said in, say, 1985. If I could find a good way of doing it. . ." How authentically angry can a millionaire pop star be? "You can be as angry as you want. As long as you don't sit around thinking, I'm a millionaire pop star.' Then you end up up your own arse." One magazine said you were worth £3 million, The Daily Express claimed you've got £10 million. Does this fascination with your money annoy you? "It's bollocks. One minute it's seven million quid, the next it's 10 million. I don't know exactly. If the chick [from the Express] who wrote that would tell me where it all is, I'd be grateful. "Money just buys you freedom. It's the only good thing I can see about it." Have you used yours well? "Yeah, I think so. I'm not mean, because I've had accusations of that. I was never interested in helicopters and big fuckin' mansions." Does your money make you feel guilty? "No. Not now, not at all. I've worked hard for it, but by the same token I've not worked as hard as, say, a doctor or a nurse. I'm aware of that." What would you say to a member of Class War if they advised you to give it all away" '"Fuck off.' The only thing I can say is, there's people who've made an awful lot more than me. "There's always this pressure to be grateful for what you've got The music business is just organised crime, for want of a better term. Fucking big time. Money goes missing, and I'm talking substantial amounts. I've seen it happen. The whole thing's a fucking rip off-totally corrupt. It's frightening. Shocking." In what way? "Like I told you: all the deals. You end up paying for all of it to make your own music, the packaging, l just had a big row recently about a video costing £40,000 -that's my trust fund for my kids, man " You've only earned a fraction of the money you've generated. Let's see- well over a dozen hit albums, scores of hit singles - you must have "made" tens of millions. "I ain't seen anything like that much. It's frustrating. I get more insulted the older I get. When you're younger, you don't think about it [The Jam's first deal netted them a princely £6,000]. Then, you're just happy to get a deal " Forward to 1993 and wild wood, which reached Number Two. Did it feel like, "I'm back'"? "I thought, I'm back on track ' I liked it, but I felt even better about the next album {Stanley Road]. After hearing it, I knew I could make an even better record. It was like a launch pad. 'Wild Wood' [title track], I really liked. 'Sunflower' was good." There's a lot of earth, wind and fire imagery on your solo albums. "Yeah-that's laziness . . . "We made Wild Wood at The Manor in Oxford, in Richard Branson's old place. That inspired me. It was the first time I'd done that, in that kind of residential setting. I always think if you want an urban record you have to make it in the city." From The Jam to The Style Council to Paul Weller, there has been a move from urban to suburban to rural. Where next-the Shetlands? "We work in town and in the country. The Manor was Just really magical. In fact, everyone who came down sensed it. A pure, one-off thing. I wouldn't particularly look for a rural setting or an urban setting. It was just right at the time. " "Moon On Your Pyjamas" was written for your son . . . "I wrote it for his fifth birthday. I managed to sing it on American radio on the same day as his birthday - it was me sending a message to him. Did he appreciate if? He will. He'll get the sentiment when he's had his own children." Would the idea of a rock star writing a paean to their child have appalled you as an angry young man? "You just wouldn't be able to understand [at that age]. Your perspective changes. "I took my two [Nathaniel, 10, and Leah, six] out last night and we were Just sitting down like friends. It was wicked. "Me and my Dad have always had a great relationship. Most of my friends have got horror stories about their relationship with their parents." Is having kids "the answer'"? "It's certainly one, and a good one But there's plenty of realities that make life worthwhile When you have kids, you have to think positively about the world. Bring them up to be decent human beings who'll grow up to make a difference." Tell me about it. What about all the violence and troubles they'll have to face? "But what are your options'? Here, have a go on this [hands over spliff]. That'll cheer you up."

Weller likes the next one, Stanley Road Really likes it. "It was the most complete thing I've ever done." Ever, ever - including The Jam and the Council? "Oh, yeah." Your albums seem to have got darker, angrier - ironic considering each one, at least up until Heavy Soul, was better and better received. "I was really surprised at the success of Stanley Road because I thought it was quite dark. I remember playing the demo to friends and they were saying, 'Take it off!'" Why was it so dark? "There was a lot of shit going down. I mean, I split up with Dee at the time " Any regrets ? "No. It makes you what you are." Has it put you off marriage? "Yeah. I'm not against it, either" Are you in love at the moment? "[pause] Yeah, I am" Where did you get all the imagery from for Wild Wood and Stanley Road, all the weavers and woodcutters and sunflowers? Were these nostalgic references to your childhood? "Only the title track [of Stanley Road] was about that. Some of those things like 'Woodcutter's Son', they kind of come from me reading stories to my kids. It was a particularly difficult time for me. . . I was just trying to write a song." Were hordes of ex-Jam fans now coming out of the woodwork? "Yeah. A lot. Which is fair enough I can understand a lot of people didn't like The Style Council. But it's not like I've gone out of my way to draw people back." "In the Nineties, I felt there was something moving again. More than anything, people went back to seeing bands. That vibe, where it's not all on tape. It's Just another generation who wanted to go out and see live music, which is important. Especially for me, because I'm a working musician. "I get so much more out of it. Things I could hear in my head I could never physically get to, but I can now. I play a lot better, I sing a lot better. Things are more consistent. But I might have said this to you in '89 or '83." You described Stanley Road as quite dark. How about Heavy Soul? "It feels like quite an angry album. Quite bare and exposed. The idea was to try and do something even more removed from Stanley Road, more rough and spontaneous. There was criticism that some of the songs were undeveloped. That was true. I wanted to write them as quickly as possible. I wouldn't say I could listen to it every day. It's a bit heavy going. It's quite uncompromising." It came out just after your 40th birthday. How was that? "All right." Then there was The Paris Hotel Room Incident (in November 1997, Weller and his six-man entourage were reported to have smashed up a room at the £400-a-night Warwick Hotel, after which he was arrested and spent the night at a local police station). What happened? "We got pissed and a bit silly. It wasn't just me. I had a fuckin' terrible hangover. I felt worse because I thought we weren't going to make the gig, which was one of the most fantastic ever. " Later that month, the music industry was rocked by hoax rumours that Weller had killed himself, amid speculation that he was depressed at the comparatively muted reaction to Heavy Soul (which had sold only 400,000 copies compared to Stanley Road's 1.5 million), and that he had found turning 40 too much to bear. His press officer, Pippa Hall, emerged from a meeting one Friday afternoon to find dozens of messages on her answer-phone: apparently, Paul had either been killed in a car crash, or he'd blown his head off with a shotgun. The following morning's Independent featured a report: "Star 'dies', is revived and then has to face Chris Evans", went the headline, referring to Weller's appearance later that evening on TFI Friday. Ironically, Michael Hutchence of INXS did take his life the very next day. Did you hear the rumour about you? "Yeah. It's true [smiles]." Was it a crisis point? "I'm at the depths of despair sometimes, but isn't everyone? I'm a very moody person. It isn't just a pose. It's a natural, physical thing." Have you ever contemplated suicide? "Everyone does, don't they? But I've got that kind of-maybe it's that old school, working-class ethic of no matter how down you get. You just get on with it. I'll be elated one day and the next day I'll be just the opposite and feel mega-bad about things. It just changes like that [click fingers]." How was turning 30? "I liked my thirties. I had a fantastic time. I was young enough to enjoy myself, but a little bit wiser and more confident. When you're younger, you want to please everybody else. Then you get to a certain age, and have a family, and that kind of makes you more selfish and self-protective, but it also bonds you [to people] because you look around and see what everyone else is trying to do. And you know that most people are pretty good." Were you affected by the death of Billy Mackenzie last year? Or Kurt Cobain's suicide? "People top themselves all the time. It's just when you're famous it's all they talk about. It must be terrible to be that much in despair and have no one to turn to. "I'm not totally sold on the idea that you have to be a tortured soul to be an artist." Did you ever hope you'd die before you got old?